Intersections of Justice and Ethics:

An Integrative-Experiential Learning Webcourse Module

Dr. Gail Sears Humiston, Ph.D.

UCF Department of Criminal Justice

As students approach graduation, it becomes increasingly important to facilitate learning beyond the classroom and create opportunities for real-world experiences in preparation for professional and civic life after UCF. Like many at UCF, students in Criminal Justice are motivated by a desire to serve their communities. In the classroom, they study issues such as race, gender, poverty, education, employment, mental health, and substance use and how social problems are related to victimization, criminal behavior, and the government’s response through the criminal justice system. In the field, criminal justice officials frequently encounter complex social problems and partner with community-based organizations to improve the quality of life for their communities.

This learning project provides a Webcourse Module which tasks students with integrating their knowledge of criminal justice, social justice, and ethical theories (Figure 1). It was developed to create a scalable, high-impact integrative learning experience to be used across different modalities and class sizes. An integrative-experiential student project like this one needs to be flexible in our department of nearly 1,400 undergraduate Criminal Justice majors with a robust online program. In this project, students are given an experiential opportunity by engaging in 15 hours of community volunteer service, as well as metacognitive and reflective learning processes, as a means of improving integrative-learning outcomes.

What Are “Integrative” and “Experiential” Learning?

As an associate lecturer and researcher, as well as former legal assistant and victim advocate, I had a general understanding of concepts of “integration” and “experience” prior to this project. In the past, I instructed Criminal Justice students on how classroom learning related to the field. However, as part of a QEP innovation project, I needed to more clearly define these concepts during the planning stage.

According to the AAC&U (2009, n.d.), “integrative” learning is designed to prepare students for professional and civic life by connecting classroom learning across the curriculum, disciplines, and beyond campus. In my mind, I felt I was already doing this in my courses. After all, traditional literature reviews are designed to target the higher levels of learning with students synthesizing prior knowledge in new, creative ways to examine unique patterns (Faculty Center, n.d.).

I surmised that the uniqueness of this project must, therefore, hinge on the concept of “experiential” learning. Experiential learning is a complex form of active learning (CEI, n.d.). This includes community-based learning as a course requirement (AAC&U, 2008). Students are provided the opportunity to have experiences outside the classroom related to the issues they are studying in the curriculum. Experiential learning requires students to reflect on their activities and engage in efforts to analyze and address community problems.

Together, the concepts of integrative and experiential learning create a high-impact educational practice (AAC&U, 2008). “Integrative experiential” learning gives students direct experience with the issues they are studying. Students set goals and plan their education. They develop self-awareness and reflect on their experiences to connect what they are learning in the classroom to real-world contexts. They are tasked with exploring and analyzing complex issues, adapting discipline specific theories and abilities, and analyzing and evaluating possible solutions to solve community problems. At UCF, courses seeking an IE course designation must meet specific criteria (What’s Next, n.d.).

Let this Module Help You Jump-Start Integrative Experiential Learning in Your Course

This project provides a viable option for online courses. The Webcourse Module can be modified to facilitate student exploration of interdisciplinary issues. It incorporates metacognitive and reflective learning processes as part of an integrative-learning experience. Students are guided through the process of planning their own learning experience and study of related factors affecting complex problems, as well as applying and evaluating theory-driven responses.

The materials provided in the Webcourse Module may be adapted for the examination of intersecting issues such as:

- Education and health

- Health and family leave policies

- Family leave policies and employment

- Employment and race

- Race and human rights

- Human rights and political governance

- Political governance and education

These issues are interdisciplinary and may be examined through a multitude of theoretical frameworks from a variety of disciplines and programs, such as:

- Psychology

- Sociology

- Philosophy

- Legal Studies

- Public Administration

- Criminal Justice

- Business

- Health

- Education

- Social Work

- Political Science

- Nonprofit Management

- Interdisciplinary Studies

Applying Integrative Experiential Learning: The Webcourse Module

The integrative-learning goals for students in this project are scaffolded. First, students identify and describe a social justice issue (i.e., behavioral health, education, environmental justice, gender justice, or hunger and homelessness) and its intersection with criminal justice (CJ). (Note: The entire class addressed the issue of racial justice in a separate module.) Second, students identify, describe, apply, and evaluate an ethical theory as a lens through which to examine their chosen societal problem and CJ’s response. These two main frameworks provide the bases for two group discussions and students’ final papers.

The experiential part of this Webcourse Module is modeled after service-learning and requires students to perform 15 hours of service in their communities as part of their exploration of a social justice issue. For example, if a student serves their 15 hours at Second Harvest Food Bank, they would focus on the social justice issues of hunger and homelessness and its relation to criminal justice. However, unlike service-learning which requires faculty to partner with organization(s), this integrative-experiential project is self-directed and tasks students with finding their own service positions.

To facilitate integrative-experiential learning, the Module consists of Webcourse pages, discussions, and assignments (see “The Final Integrative-Experiential Webcourse Module”). Several pages collectively inform students of the goals and steps of integrating their knowledge of a social justice issue that intersects with CJ and evaluation of an ethical theory. The discussions and assignments detail their respective learning requirements.

An Experiential-Learning Handbook facilitates the students’ learning process (see “The Final Integrative-Experiential Webcourse Module”). The Handbook walks students through the metacognition and reflective processes of integrative-experiential learning. It consists of four sections that:

- describe the purpose of integrative-experiential learning;

- address workplace ethical issues and dilemmas;

- educate students on setting goals and planning learning; and,

- instruct them on keeping a journal for reflective learning.

The Handbook includes several organizational web links for students to seek and secure service positions in the community. It also instructs students on completing their Experiential Service-Learning Commitment (see “The Final Integrative-Experiential Webcourse Module”) for upload to a Canvas assignment portal and instructor approval.

The Evaluation of Integrative-Learning Outcomes

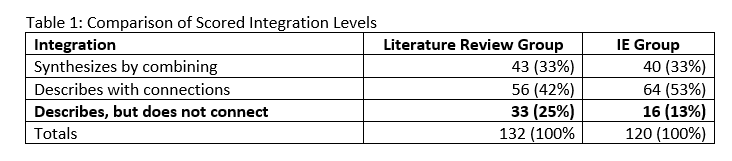

The creation and implementation of this Integrative-Experiential Webcourse Module was part of a QEP innovation project. A quasi-experimental design was used to examine integrative-learning outcomes when comparing students assigned to a learning experience versus a traditional literature review. Data was collected in fall 2018 and spring 2019. The sample consisted of upper-level CJ undergraduates (N=252). Six course sections were randomly assigned to either the experiential-learning group (n=120) or literature review group (n=132).

A modified version of the AAC&U Integrative-Learning VALUE Rubric was used to measure “integrative learning” (AAC&U, 2009). All students had been assigned papers to integrate their chosen social justice issue that intersects with CJ and an ethical theory. Three levels of integration were used to assess students’ final papers assigned to both groups. The three levels were:

3 = Creates a whole out of multiple parts (synthesizes) or draws conclusions by combining a description of a social justice topic, its relation to criminal justice, and evaluation of an ethical theory.

2 = Describes and connects a social justice topic, its relation to criminal justice, and applies an ethical theory, but does not synthesize by combining.

1 = Describes a social justice topic, its relation to criminal justice, and describes an ethical theory, but does not make connections.

When comparing integrative-learning outcomes on students’ final papers, those in the experiential learning group were less likely to score at the poorest level, as compared to students in the literature review group (see Table 1).

This result suggests that using experiential teaching methods in conjunction with metacognitive and reflective learning processes improves integrative learning outcomes. This finding is particularly important for our CJ students who reported in a separate survey (n=178) that they enrolled as transfer students (78%), have received a Pell Grant in the past (58%), work 31 or more hours each week (43%), and attend UCF full time (86%).

Students’ perceptions of the integrative-experiential capstone project were mostly positive. Students’ generally commented that they felt the experiential learning was interactive and useful. They appreciated connecting ethics beyond the classroom. A few stated they would continue volunteering.

Those students who viewed experiential learning negatively had difficulty fitting in the volunteer hours due to conflicting demands on their time. One option of accommodating students’ preferences is to offer them a choice between an integrative-learning experience or traditional literature review project.

Conclusion

The final integrative-experiential module is designed to be a scalable, high-impact experience to be used across modalities and class sizes. It scaffolds learning by progressing students through a series of Webcourse pages, discussions, and assignments which gradually move students from the lower levels of learning (i.e., describing a social justice issue and its relation to criminal justice) to the higher levels (i.e., applying and evaluating an ethical theory). At the end of the Webcourse module found below, a set of in-class group activities for live “flipped” courses is also provided.

The module includes an Experiential-Learning Handbook that walks students through the critical learning processes of metacognition and reflection, as well as listing several organizational web links for service positions in the community. Students secure their own community service experiences, allowing them more freedom to find positions of greater interest to them. Hopefully, other faculty will see that this project is generalizable to their disciplines. It allows students to explore their local communities and communicate how their UCF coursework translates into problem-solving approaches beyond the campus and into the future.

Dos and Don’ts

- Do include explicit integrative-experiential learning objectives in the course syllabus.

- Students need to be aware of the unique expectations to successfully complete the course.

- Do include the metacognitive process of requiring students to write their professional and civic goals, learning objectives, activities, information sources, and methods of assessments.

- Get students on track early by providing clear instructions and written examples of short- and long-term goals and learning plans to help them understand the project’s purpose and process.

- Do include at least one structured reflection assignment for students to expressly connect their experiences to ongoing professional and civic goals and learning outcomes.

- Do include class discussions that scaffold progression to the final paper and allow students to share their experiences.

- Discussions allow stronger students to model their efforts and share examples with others who may benefit from and be influenced by their peers.

- Discussions allow students to interact with each other to share diverse experiences and perspectives.

- Discussions provide opportunities for students to articulate their knowledge and experiences to their peers before communicating them to audiences beyond campus.

- Don’t worry that you can’t verify each and every student’s community service hours.

- By having students provide evidence of their 15 hours of community service prior to instructor approval, they are much more likely to follow through with their promises to other organizations.

- Remind students that employers are looking for community-minded applicants with good work ethics, social skills, and practical knowledge of complex societal issues. By volunteering in their community, they can add the experience to their resumé, ask the community supervisor for a reference, and take the initiative to discuss their project during job interviews.

- Do have a back-up plan for students unable to complete the 15 hours of volunteering.

- External events, such as hurricanes and the novel coronavirus, are beyond our control. You want students to have a way to successfully complete the course.

References

Association of American Colleges and Universities [AAC&U]. (2009). Integrative Learning VALUE Rubric. Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics/integrative-learning

Association of American Colleges and University [AAC&U]. (2008). High-Impact Educational Practices. Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/leap/hips

Association of American Colleges and Universities [AAC&U]. (n.d.) Leading Initiative for Integrative Learning. Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/leading-initiatives-integrative-learning

Center for Educational Innovation [CEI]. (n.d.). Active Learning. University of Minnesota. Retrieved from https://cei.umn.edu/active-learning

Faculty Center. (n.d.). Bloom’s taxonomy. Retrieved from https://fctl.ucf.edu/teaching-resources/course-design/blooms-taxonomy/

What’s Next. (n.d.). Integrative-Learning Experience Course Designation. Retrieved from https://undergrad.ucf.edu/whatsnext/faculty-staff/integrative-learning-experience-designation/

The Final Integrative-Experiential Webcourse Module

- 1. Syllabus

- 2. Introduction to Capstone Projects: Intersections of Criminal and Social Justice (Webcourse page)

- 3. Purpose of Module & Choice of Social Justice Issue (Webcourse page)

- 4. Integrative Learning Experience & Handbook (Webcourse page)

- a. Experiential Learning Handbook (Word version) (attachment)

- b. Experiential Learning Handbook (pdf version) (attachment)

- 5. Inspirational Videos on Social Justice Topics (Webcourse page)

- 6. Intercept Model (Webcourse page)

- a. Sequential Intercept Model (attachment)

- 7. Choice Between Social Justice Topics – Choose Carefully! (Webcourse page)

- 8. UCF’s Youth Protection Program – When UCF Requires a Background Check (Webcourse page)

- 9. Integrative Experiential Service-Learning Commitment Cover Sheet & Worksheet – (Service Position must be Approved Prior to Serving Community) (Webcourse assignment)

- a. Learning Commitment signature form (Word docx attachment)

- 10. Instructor's Notes on Creating Groups and & Discussions (Webcourse page)

- 11. Join a “Social Justice” Group Here! (Discussions will be “published” in this module after everyone has joined a “Social Justice” group) (Webcourse assignment)

- 12. Description of Discussion 1 (This is NOT the actual discussion portal) (Webcourse page)

- 13. Description of Discussion 2 (This is NOT the actual discussion portal) (page)

- 14. Social Justice Discussion 1 (NOTE - This IS the actual Discussion portal) (Webcourse discussion)

- 15. Social Justice Discussion 2 (NOTE - This IS the actual Discussion portal) (Webcourse discussion)

- a. Discussion Grading Rubric

- 16. Reflection Journal – (15 Hours of Service are to be Completed by this Due Date) (Webcourse assignment)

- 17. Bibliography (Webcourse assignment)

- 18. Experiential Paper (Webcourse assignment)

- a. Finding Articles (Webcourse page)

- b. Citing and Summarizing an Empirical Article (and a reminder about plagiarism) (Webcourse page)

- c. Article Summary Outline (Word docx attachment)

- 19. In-class Group Activities Portfolio (8 group discussions)