The Effects of High-Impact Practices Integrated

in a Leadership Living Learning Community

Dr. Stacey Malaret,

Director of LEAD Scholars Academy

Desia Bacon

Undergraduate Teaching Assistant

Alexis Szelwach

Undergraduate Teaching Assistant

Abstract

As a college student in a new environment, establishing a healthy independent sense of self is dependent on a sense of belonging. A sense of belonging is defined as the “psychological sense that one is a valued member of the college community” (Hausmann, Schofield, & Woods, 2007, p. 804). Living Learning Communities (LLCs) are one way for students to overcome the difficulty of finding a sense of community on campus. By facilitating the opportunity for students to become part of a smaller grouping where a sense of community is already established, LLCs help students adjust to college life and more easily develop their sense of belonging. Through the use of focus groups, statistical data, and through literature review, this study analyzes the use of the high-impact practices within the LEAD Scholars Academy. These findings demonstrate a higher-than-average retention rate for students and suggest ways for other units and programs on campus to increase retention, not only to a LLC but to the university more generally. The findings show the importance of a strong curriculum within on-campus LLCs and similar programs. By combining psychological theory and research in higher education, this study allows for a better understanding to the first-year success and experience within a LLC.

The LEAD Scholars Academy is an undergraduate leadership development program that targets rising first-year students with high academic achievement, leadership potential, and a passion for community service. High school seniors apply to the academy the spring semester prior to graduation. LEAD Scholars Academy is a selective program, vetting applicants according to academic achievement, standardized test scores, previous leadership positions, breadth of club and organization involvement, and community service experiences. Student applicants complete a resume, essay, project, and phone interview and are reviewed in spring/early summer each year on a rolling admission process.

George Kuh (2008) defines high-impact practices as those that “educational research suggests increase rates of student retention and student engagement” (p. 9). According to Kuh, HIPs are experiences that focus on faculty interaction, diversity experiences, integrate learning, provide real-world learning, required invested time and effort and include frequent feedback such as undergraduate research, study abroad, Capstone experiences, and Living-Learning Communities. LEAD Scholars Academy offers various high-impact practices and co-curricular opportunities to encourage learning development and community building amongst the student cohort. LLCs are, themselves, considered high-impact practices, but LEAD Scholars Academy includes a number of additional HIPs, including: a pre-collegiate transition retreat, a first-year seminar course, a capstone course, undergraduate research opportunities, service-learning classes, mentoring experiences, student leadership opportunities, etc. First-year students enroll in a two-credit-hour Introduction to Leadership class in the fall and Intermediate Leadership class in the spring semester of their first year. Their second year includes Advanced Leadership and Capstone class experiences. All four courses are service-learning designated courses and require at least 15 service hours. Students also complete co-curricular leadership workshops in order to stay in good standing with the program. Students in good standing receive a $200 fellowship and access to private endowed scholarships intended for LEAD Scholars. Previous analyses have shown that high impact educational practices, such as learning communities, have particularly positive benefits for first-year students (Kuh, 2008).

Kuh (2008) stated, “The key goals for learning communities are to encourage integration of learning across courses and to involve students with ‘big question’ that matter beyond the classroom. Students take two or more linked courses as a group and work closely with one another and with their professors. Many learning communities explore a common topic and/or common readings through the lenses of different disciplines. Some deliberately link “liberal arts” and “professional courses”; others feature service learning” (p. 10).

Literature Review

Students are offered the choice when entering college to live in unique communities distinguished as Living Learning Communities (LLCs), which are also known as Residential Learning Communities. These communities foster environments in which students are given curriculum in their given major or area of interest that facilitates their engagement and academics. “Learning communities, in their most basic form, begin with a kind of co-registration or block scheduling that enables students to take courses together, rather than apart” (Tinto, 2003, p.1). These students are interlocked with one another and develop as a cohort throughout their year of living on campus and learning in their designated program (Tinto, 2003).

LLCs date back to the start of the 1920s when there was an experimental version of a college community that was put into place. The idea was revised in the 1960s but the version of these communities that we know today was modernized in the 1980s. After this time it was proven that a student’s performance increased if learning occurred both inside and outside of the classroom. The dual level of engagement and recognition not only enhanced academic performance, but became an intellectual indicator of extracurricular and academic performance. Students with like-minded interests are usually attracted to a particular type of community, and it reflects in their group norms and performance. (Meih Zhao & Kuh, 2004).

College is a time when many students are living without direct parental supervision for the first time and, likewise, encountering people with diverse backgrounds and world views; it is a time when students form a revised, independent sense of self. Feeling a sense of belonging in this new environment is particularly important to a student’s ability to develop a healthy independent sense of self. A sense of belonging is defined as the “psychological sense that one is a valued member of the college community” (Hausmann, Schofield, & Woods, 2007, p. 804). A sense of community is defined as “a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met” (McMillan & Chavis, 1986, p. 9). A university can be an overwhelming environment, and finding a way to be a part of the campus community can be difficult for students. Programs that provide students with a supportive community can help them navigate these challenges.

LLCs are one way for students to overcome the difficulty of finding a sense of community on campus. By facilitating the opportunity for students to become part of a smaller grouping where a sense of community is already established, LLCs help students adjust to college life and more easily develop their sense of belonging. Research shows that undergraduate students with a strong sense of self and a sense of community benefit from many positive outcomes (Spanierman et al., 2013). These positive outcomes have been determined through numerous multi-institutional studies (Lounsbury & DeNeui, 1996; Johnson, 2007; Johnson et al., 2007). A sense of belonging is pivotal for student success and retention, and these Living Learning Communities facilitate that through providing social and academic support in ways that traditional residential experiences do not (Spanierman et al., 2013).

Students living on campus have higher academic outcomes between their first and second year of college, and higher university engagement in co-curricular activities, faculty engagement, and peer interactions (Cruce et al., 2008). Living Learning Communities are effective in providing a collegiate experience that facilitates these types of experiences (Bewley, 2010). Students self-select where to live on campus and, furthermore, self-select whether they want to live in a LLC in campus residential housing; therefore, it is hard to determine whether the LLC variable is the variable that leads to student success, or a combination of other variables (i.e. socioeconomic status, high school, etc.).

“Being the RA of the Lead LLC is a unique experience. We are a part of what I like to call the transition for students. When describing the college experience, I often tell students that it isn’t good or bad, it’s just different. We help them not only understand themselves but also each other. What is unique about LEAD is that you get to work with students who already have something in common. They all wish to be great leaders. As the RA, I use this as the starting point to help them form deep connections with themselves and others. With the help of LEAD Scholars, I am able to create events tailored toward their success and promote connections with the floor mates.”

-Darwins Olcima, Senior, LEAD LLC RA

One key component that makes these communities so powerful is the act of sharing: not only knowledge, and knowing, but responsibility. Each academic component in an LLC creates a linked curriculum that intertwines the program’s curriculum and goals. Students who live in a LLC share both the academic component of the residential curriculum, created by the Housing and Residence Life office and leadership studies curriculum learned in LDR classes with LEAD Scholas Academy. These academic components are enhanced by co-curricular opportunities available to the community through LEAD Scholars Academy including service, educational workshops and social opportunities. The “linked” curriculum helps to create bonds with faculty as well as with peers in order to strengthen the students’ connections to the community and their chosen disciplines. The aspect of shared responsibility within the community has been connected to higher retention and classroom participation. It allows students not only to become more engaged in the classroom but to become active citizens within their community, increasing involvement drastically (Steir, 2014).

Although students are a key component of this experience much of the responsibility falls to the student affairs staff who oversee the LLC. Research has also proven that faculty who participate in service-learning, and team-building activities (both academic and social) foster higher rates of engagement inside the classroom. Students feel better connected to the program and community when faculty and staff allow them to interact as equals (Steir, 2014).

Engaging in seminars, retreats, and intertwining curriculum is one way to advise students in a new exciting way, but always create the sense of belonging and community that students seek in living in a learning community. They feel more connected to each other but identify with the curriculum on a deeper level, influencing their involvement, as well as their retention (Steir, 2014).

Schlossberg’s theory of transition posits that a student’s transition from high school to college is a complicated time for students that requires support from universities. And, studies have born out this theory. For example, Alison TePoel at the University of Nebraska, studying the Chancellor’s Scholars’ Program, an LLC very similar to LEAD Scholars Academy, found, using Schlossberg’s theory, that the four S’s (situation, self, support, and strategies) were instrumental for the students who were a part of this program. These students were retained at a higher rate than the general population of first-year students and also felt more connected and engaged to their community and school (TePoel, 2012).

Methodology

The LEAD Scholars Academy studied LLC students who currently reside or resided in Neptune Building 157. The 45 who completed the survey were current first-year and second-year students at UCF in LEAD Scholars Academy. Focus group participants (n=11) were also UCF students who lived or previously lived in the LLC. . Each student had the opportunity to participate in focus groups and answer surveys. Students volunteered to participate, and were not specifically selected based off sex, age, or race/ethnicity.

Students who participated in the assessment process were provided information regarding the research study and survey instruments. Students volunteered to participate in the focus group and had the opportunity to complete the four-page survey at the end of the spring 2017 semester. Eleven students participated in the focus group, chose an alias to use during the discussion, and completed the optional questionnaire. The focus group discussion was recorded by the investigators and was transcribed later. Surveys were distributed during the focus group, emailed to all eligible participants, and distributed in their residence halls.

The authors acknowledge that there may be differences in responses from students in the focus groups and in the survey responses due to the date the focus group was held or the survey was responded to. The students requested more social programming in the fall focus group, and this was implemented beginning in the second month of the spring semester. These social programs may have improved the responses of the students to questions posed. It was noted in the transcription of the later focus groups that students were responsive to the introduction of social programming because it facilitated more relationships amongst their peers and led to a stronger sense of belonging. The differences could also be attributed to the students living in the community longer, giving them more time to build relationships with their peers and become more involved in the leadership program at large. Also, there was a larger number of responses for the paper survey than the focus group and students who attended the focus group tended to be the more involved and tight-knit group. The authors can also attribute some of the improvement of student responses to their time spent immersed in their service learning curriculum. The students have spent a longer time in college as a whole, possibly making them just more comfortable with the university, and within the niche of their living community.

Data

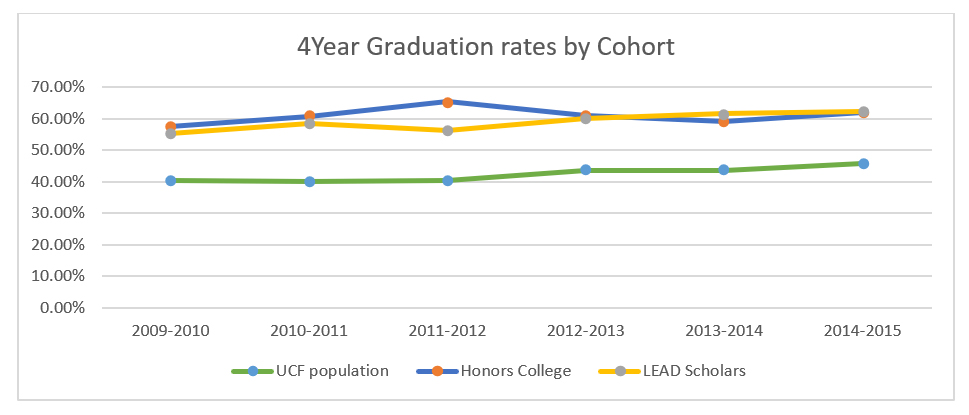

In Table 1 LEAD Scholars Academy students are compared to honors college students and their FTIC cohort in four-year graduation rates. LEAD Scholars had a higher graduation rate in comparison to FTIC students each year and a comparable rate to the honors college students.

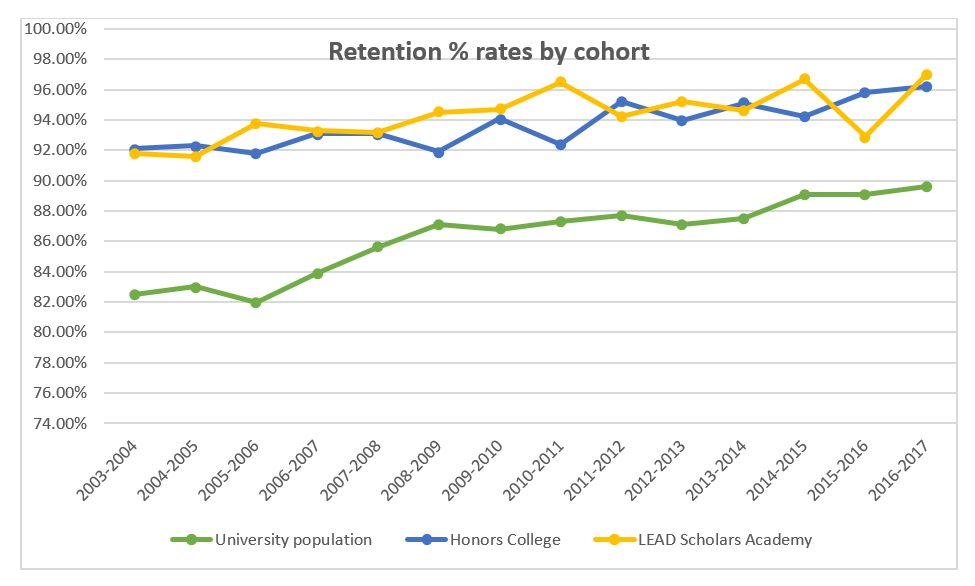

In Table 2 LEAD Scholars Academy students are compared to honors college students and their respective FTIC cohort in retention rates. LEAD Scholars had a higher or equal retention rate in comparison to honors college students in ten out of the fourteen cohort years. LEAD Scholars exceeded the FTIC retention rate in every year by more than 7 percentage points each year.

Research Design

This research concurrently utilized surveys and focus groups to complement the surveys; 45 participants (35 female, 9 male, 1 other) completed the questionnaire, and 11 participants participated in the spring 2017 focus group (6 female and 5 male). Some participants (n=11) participated in both. The questionnaires consisted of two sections. Section 1 contained nine multiple choice questions focused on demographics and housing. Section 2 contained 22 roles (participation and leadership) and relationships questions, all of which were answered on a scale from 1–5 (1= “strongly disagree” and 5 = “strongly agree”). For the survey questions from Section 1: see Appendix A, Table 1; from Section 2: see Appendix A, Table 2.

The focus group lasted approximately an hour and a half, with the amount of time varying in order to allow students to freely and fully answer questions presented by the researchers. Students were each referred to as an animal name to protect their identity. The researchers asked a series of predetermined questions based on considerations made early on in the project. The researchers acted as moderators, maintaining control over the discussion by setting the ground rules for the focus group, introducing each new discussion topic, and probing/interjecting when necessary to make sure the conversation remained focused on the goal questions. There was variation in the amount of time spent on each question based on how participants responded. The transcript record of the focus groups further indicates the latitude that allowed free discussion of the questions and issues amongst participants, leading to unanticipated opinions and responses. Though there are these variations, the focus group discussion was relatively structured used guided questions for the focus group.

Discussion

In the focus group, several LEAD Scholars Academy co-curricular and high-impact practices were cited by participants as having helped them build community. Participants repeatedly mentioned the REEL (Residentially Enhanced Experiential Learning) Retreat. The REEL Retreat is an overnight transition retreat for incoming first-year students which takes place off campus. This retreat includes community-building activities, leadership lessons, and a low-ropes course. Students stated that this two-day retreat assisted them in building long-term friendships, learn about LEAD Scholars, and become acclimated to the LEAD Scholars Academy culture. Secon- year students serve as REEL counselors for the first-year students and are trained on reflection and facilitation techniques prior to the retreat. Some students cultivated a sense of belonging and relationships with their peers in the retreat, prior to beginning their stint living in the leadership learning community, which allowed them to form deeper friendships. More in-depth research in the positive outcomes associated with a pre-collegiate transition retreat is warranted based on this feedback.

Another topic that was popular during the focus group was the Summer B Social that LEAD Scholars Academy hosted in late June for students who were admitted in the summer semester. This allowed students to meet other LEAD Scholars prior to the fall cohort starting and allowed community building to start early in their college career. The office is also open all summer so Summer B students were able to learn about these resources at the social.

Students also spoke about the available third- and fourth-year programs. They liked the opportunity for transfer students, who did not have the ability join LEAD as first years, to still be involved in high-impact practices within LEAD.

Some areas of improvement that the students mentioned included the need for new programming to be implemented, more social programming outside of the academic curriculum, and other bonding opportunities within the LLC. They also wanted to stay connected in housing and wanted longer options to live in a housing community as a cohort beyond the first year. They also wanted more time in service-learning classes. The authors speculate that students will have a better sense of self and service areas of interest, be more involved on campus, and have more leadership positions if service-learning opportunities are increased.

Data From Surveys

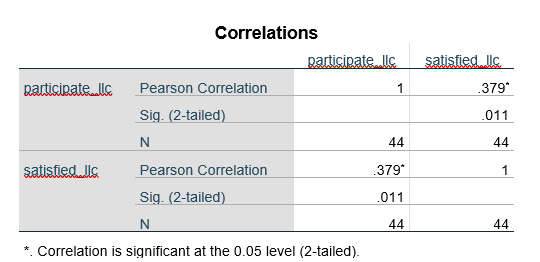

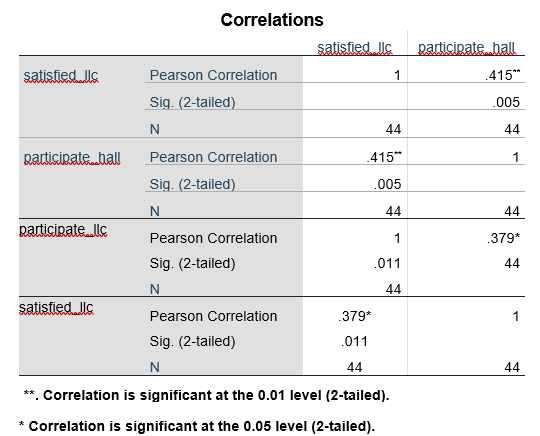

The study intended to learn if students who resided in the LLC were active in LLC activities and were satisfied with the overall LLC and participated in co-curricular events offered. Pearson product-moment correlation was run to determine the relationship between LLC activity participation and overall satisfaction with the LLC. There was a strong, positive correlation, which was statistically significant (r = .379, n = 44, p = .011).

Conclusion

Students who participate in LEAD Scholars Academy and a living learning community in their first year were found to be more engaged with their peers as well as their community than first-year students who did not. Retention rates and GPA scores also tend to be higher for LEAD Scholars Academy students compared to the general population. Students in the focus group said they found their sense of belonging and purpose as a result of living in the LLC for LEAD Scholars and practicing what they learn in both their classroom and the curriculum through Housing and Residence Life.

High-impact practices benefit not only the students who participate in them but the university at large. Through service, in-class activities, and learning within their living spaces, these students have not only been retained to the university at a higher rate but have been more engaged citizens. These findings should lead to further plans of actions including but not limited to: 1) Expand the availability of LLCs to all FTIC students so that every student will have opportunities to participate in high-impact practices inside and outside of the classroom. 2) Mandate students to participate in high-impact practices in both their first and senior years, in order to increase their involvement and grade point averages. 3) Create a policy and continue research to allow for all FTIC students to be mandated to live on campus so that they are exposed to high-impact practices from their first day starting at a university. Not only would this serve as a catalyst to helping reach a higher retention rate, but psychological research demonstrates that it would help students better connect to their university. 4) Improve how various high-impact practice programs across campuses implement their LLC programs. Through using the practices of the LEAD Scholars Academy, this may increase overall retention, academic success, and involvement for all students.

UCF departments can strive to replicate the experiences in a LLC without a housing experience. Involving students in a specific major with other co-curricular high impact practices like service-learning, undergraduate research, study abroad, etc. can help a student find their sense of belonging at UCF. Starting with an onboarding process like a retreat or extended orientation can help set the stage for community amongst their peers. Also, academic advising can pair students in a cohort and help them find class sections where students are surrounded by their peers taking the same classes. Involving the UCF Student Academic Resource Center (SARC) or Supplemental Instruction (SI) can also help students find outside of class experiences to enhance what they have learned in the classroom in a peer-learning environment. Partnering with Career Services and Experiential Learning can help students further along in their academic path get ready for post-graduation. Creating opportunities for cohorts to go through these workshops or experiences together allows them to have a cohort to ask questions and lean on for support. Simply put, allowing students to gather and interact outside of the classroom with like-minded peers helps create a sense of community and belonging.

“My favorite thing about the LEAD LLC is the fact that I’m in such close proximity to dozens of other LEAD students. While that’s obviously the point of the LLC, it was very beneficial to me when I first moved to UCF and had no close friends here. For the first couple of weeks, I only left my dorm to eat, go to class, and go to Marching Knights practice. But thanks to the LLC, I quickly made friends on my floor that helped me get more involved with LEAD and other organizations at UCF. Now, I constantly hang out and study in the LEAD lounge, and the only times I’m ever in my dorm throughout the day is when I wake up and when I got to sleep. I’m very grateful for the great friends and opportunities that the LLC has given to me, and I would definitely recommend it to any incoming LEAD students!”

-Nicholas McCutcheon, First-Year, LEAD LLC Resident

References

Bewley, J. L. (2010) Living-Learning Communities and Ethnicity: A Study on Closing the Achievement Gap at Regional University (Order No. 3417733). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; ProQuest Social Sciences Premium Collection. (746481549). Retrieved from https://login.ezproxy.net.ucf.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/746481549?accountid=10003

Cruce, T.M., Gonyea, R.M, Kuh, G.D., Kinzie, J., & Shoup, R. (2008). Unmasking the effects of student engagement on first-year college grades and persistence. The Journal of Higher Education, 79, 540-563.

Foubert, J. D., & Urbanski, L. A. (2006). Effects of Involvement in Clubs and Organizations on the Psychosocial Development of First-Year and Senior College Students. NASPA Journal, 43(1). doi:10.2202/0027-6014.1576

Hausmann, L. R. M., Schofield, J. W., & Woods, R. L. (2007). Sense of belonging as a predictor of intentions to persist among African American and White first-year college students. Research in Higher Education, 48(7), 803–839

Johnson, D. (2007). Sense of belonging among Women of Color in science, technology, engineering and math majors: Investing the contributions of campus racial climate perceptions and other college environments (Doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park). Available from ProQuest. Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. AAT 3297338).

Johnson, D.R., Soldner, M., Leonard, J.B., Alvarez, P., Inkelas, K.K., Rowan-Kenyon, H., & Longerbeam, S. (2007). Examining sense of belonging among first-year undergraduates from different racial/ethnic groups. Journal of College Student Development, 48(5), 525–542.

Lounsbury, J. W., & DeNeui, D. (1996). Collegiate psychological sense of community in relation to size of college/university and extroversion. Journal of Community Psychology, 24(4), 381–394.

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What are they, who has access to them, and why they matter. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Personality and motivation. New York, NY: Harper. McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community. Psychology, 14(1), 6–23.

Spanierman, L. B., Soble, J. R., Mayfield, J. B., Neville, H. A., Aber, M., Khuri, L., & De La Rosa, B. (2013). Living learning communities and students’ sense of community and belonging. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 50(3), 308–325. doi:10.1515/jsarp-2013-0022

Stier, M.M., “The Relationship Between Living Learning Communities and Student Success on First-Year and Second-Year Students at the University of South Florida” (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations

TePoel, A. P. (2012). Chancellor’s Scholars Program: Exploring the Transitional Influence on

Freshmen College Students (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Nebraska-Lincoln.doi:http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1089&context=cehsedaddiss

Tinto, V. (2003). Learning Better Together: The Impact of Learning Communities on Student Success. Higher Education Monograph Series 2003(1). 1-8

Zhao, C.M.; Kuh, G.D. (2004). Adding Values: Learning Communities and Student Engagement. Research in Higher Education, 45(2), 115-138