COS Exploration: Advising Conversations About

Degree-Completion Burnout

Dena Ford, M.A.

Academic Advisor IV

College of Sciences

If you’ve worked with students in an advising role then it is likely that you’ve encountered students who are struggling with their career path or with broader concerns about their future. I developed an approach in the College of Sciences Advising Services (COSAS), and this article will describe a few techniques from the COS Explore program. These techniques offer an integrative learning approach that encourages intentional learning and that can be used in the classroom.

Advising-session conversations with students who reported degree-completion burnout have inspired programming that helps them to reevaluate their goals. When we asked students about their academic goals we encountered responses from students such as “this degree is for my parents” or “I don’t want a job in this field anymore but I’m so close to finishing, and I just want out”, and when asked about their academic goals we opened the door to student-centered narrative techniques in an advising setting. Narrative techniques allow students to revisit their values, interest, and skills that connect with their own personal experiences. The purpose of the Sciences Exploration program (COS Explore) is to retain undergraduate students who may be in academic decline at the University.

COS Explore is an academic intervention program for students who are not meeting their major’s minimum GPA requirement, and due to their declining science GPA, they are at risk of academic probation. This program uses a narrative approach, which can easily be transferrable into any curriculum by offering complementary assignments requiring students to apply concepts learned in the classroom to their own lives. For instance, as students are introduced to new concepts, a subsequent journaling prompt such as ‘how does this concept apply to your career-related values or goals?’ can help build academic confidence through the students’ professional developmental process.

An institutional (UCF credit only) GPA of 2.0 is required for a student to be in good academic standing, according to University policy, even though many degree programs have stricter GPA requirements. This means that many students who are struggling with degree-completion burnout may actually be in good academic standing according to the university policy, and thus, may not receive outreach or intervention efforts through the University. Students in this “gray area” are then expected to navigate through University resources by themselves. This can lead to dire consequences if students in “good standing” are not meeting their major GPA requirements and apply for graduation. If all credit requirements are met, but the major GPA is not met, a degree may not be awarded. The COS Explore academic intervention efforts were implemented in the College of Sciences at the start of fall 2013 to help prevent such unfortunate situations by intervening prior to the graduating term.

Even though COS Explore was developed in an advising setting, the framework can be applied in any classroom setting by incorporating narrative journaling techniques with benchmark assignments. Narrative techniques that focus on values, interest, and skills, as well as roadblocks in students’ education can help to stimulate motivation. Narrative techniques offer students guidance to construct individual pathways by self-identifying life themes, cultural experiences, influences, and decision-making cycles (including indecisions) (Brott, 2001; Savickas, Nota, Rossier, Dauwalder, Duarte, Guichard, van Vianen, 2009). Narrative career counseling techniques were used in the advising setting to explore academic and career goals as well as alternative majors outside of STEM. Academic intervention objectives designed for curriculum-specific assignments, along with implementation strategies, could be identified by department faculty. Faculty and departments may consider collaborating with their College’s professional advising team to determine if and how their college currently intervenes with students on academic probation. Declining student grades combined with narrative journaling outcomes that imply academic burnout may be characteristics of a student at risk or on academic probation, or in need of an advising conversation.

Data Analysis

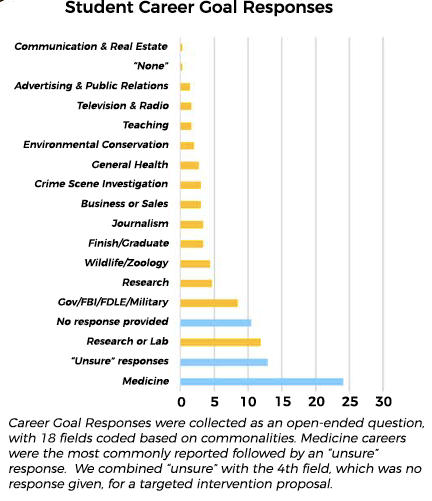

This analysis offers empirical evidence of successful academic intervention techniques and programming. These data were collected from fall 2013 to fall 2015 through a Student Self-Assessment, and includes a total of 289 undergraduate student responses. At the start of the intervention (beginning of first session), 24% of the students stated that they were on a pre-med, or pre-medicine, track when asked to identify their career goals. This was an open-ended question, and 18 career fields were coded based on their responses (see the Student Career Goal Responses in Table 1 for a graph of all 18 career fields). A medicine track career was by far the most common career goal, and the second most common response to this question was either an “unsure” statement or no response, which combined is also at 24% (these responses were combined in this report to show the need for a targeted intervention). Following the intervention and as of the start of summer 2018, 43% of the students switched their major and 55% have graduated from UCF. When the total population was asked on the Student Self-Assessment inventory to specify factors that led toward academic decline, 30% of the students expressed elevated familial pressure (percentage represents ratings 6–10 on a Likert Scale of 1–10), 65% stated that they would not have sought help on their own, and 57% expressed elevated anxiety associated with their coursework load (percentage represents ratings of 6–10 on a Likert Scale).

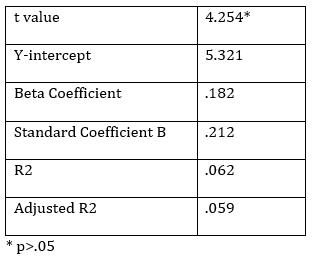

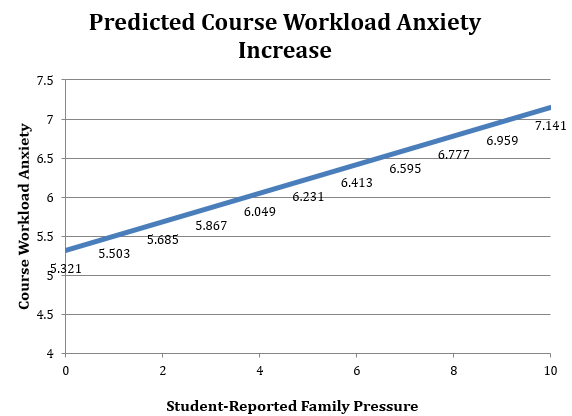

Demographics of this student population included 44% who self-identified as transfer students, and 64% self-identified as first-generation college students. Finally, 65% were female while 35% were male. We were able to verify this information through PeopleSoft tracking. Students’ race was included (defined by institutional race options on admission applications) in the data analysis: 40% White, 29% Hispanic, 18% Black/African American, 7% Asian, 4% Multi-Racial, 1% Non-resident Alien, 1% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 1% were not specified. Using the outcomes of student responses provided to the Likert Scale questions that asked students to rate their familial pressure and to rate their course workload anxiety, a linear regression equation was created using the beta coefficient and Y-intercept (see Table 2) to illustrate predicted outcomes. Table 3 highlights the predicted impacts on course workload anxiety that students feel when familial pressure is elevated.

Based on these findings, I am able to recognize additional interventions to identify and support students in danger of degree-completion burnout. Indicators of potential degree burnout include students who are self-reporting that they are unsure or not able to respond to questions pertaining to career interest related to their major selection. Likewise, students who have selected a major but expressed uncertainty about how skills learned will be applied to a career may be at risk of degree-completion burnout. A key finding in the data analysis outcome showed that students are experiencing high levels of anxiety related to major selection and family pressure. Based on this information, I am able to have meaningful conversations with students to encourage them to have open discussions about the impacts of chronic anxiety (e.g., declining GPA, or not meeting the major GPA minimum) with family members, and to ask for support, both at home and through university resources.

Faculty and staff in disciplines across campus who wish to engage their students in a dialog that ignites goal-setting related to professional development can consider narrative techniques through journaling prompts. For instance, an integrative learning prompt such as What is your career goal, and how does this course [assignment] play a part in your career path? can help students re-visit both steps completed and steps yet to be accomplished in their own path. Short and tangible responses can be encouraged to help guide students toward measurable responses that offer substance to their experiences. Table 1 offers responses from a similar question that students are asked in the COS Explore program (What is your career goal?). I found that while asking these questions, it is important that students recognize pitfalls and triumphs that they’ve experienced along the way. The narrative approach necessitates self-identifying meaningful life themes and experiences that help to shape personal and professional development.

References

Brott, P. E. (2001). The Storied Approach: A Postmodern Perspective for Career Counseling. The Career Development Quarterly 49, 4, 304–313.

Savickas, M. L., Nota, L., Rossier, J., Dauwalder, J.P., Duarte, M.E., Guichard, J., Soresi, S., Van Esbroeck, R. & Van Vianen, A.E.M.. (2009). Life Designing: A Paradigm for Career Construction in the 21st Century. Journal of Vocational Behavior 75, 3, 239–50.